Microbiology encompasses the study of diverse microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, each of which requires specialized culturing techniques to isolate, propagate, and analyze them effectively. Culturing remains a cornerstone of microbiological research and diagnostics, enabling the identification of pathogens, assessing antimicrobial susceptibility, and exploring microbial ecology. Despite advances in molecular methods, traditional culturing provides irreplaceable insights into viability, phenotype, and interactions that genomic approaches alone cannot capture. For instance, in clinical settings, bacterial cultures from blood or urine samples are essential for confirming infections, with studies showing that proper culturing can achieve recovery rates of 50-80% for common pathogens, though less than 10% for unculturable species like Mycobacterium leprae. Globally, estimates suggest there are 1.5 to 5.1 million fungal species, but only about 150,000 have been described, with culturing success rates varying from 5-70% depending on habitat and media, highlighting the gap between known and uncultured diversity. Viruses, as obligate intracellular parasites, pose unique challenges, often requiring cell cultures where yields can reach 10^6 plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/mL) in optimized systems, but success depends on host cell compatibility.

The history of culturing traces back to pioneers like Robert Koch, who in the 1880s developed solid agar media to isolate pure bacterial cultures, revolutionizing the field by allowing the fulfillment of Koch’s postulates for proving pathogenicity. In virology, the 1940s saw the advent of animal cell cultures, which facilitated the isolation of viruses like poliovirus, leading to vaccine development. Fungal culturing evolved similarly, with techniques like moist chambers enabling the study of ascomycetes and hyphomycetes from environmental samples. Today, challenges persist: approximately 50% of bacteria remain unculturable in standard media due to intracellular lifestyles or nutrient dependencies, while fungi in extreme environments like deep-sea sediments yield only 10-20% culturable isolates per sample. This article provides detailed, step-by-step methods for culturing bacteria, fungi, and viruses, incorporating real data from studies on yields, recovery rates, and challenges to ensure accurate, reproducible results. By emphasizing aseptic practices and tailored conditions, microbiologists can minimize contamination, often ranging from 5-15% in nonselective media, and maximize outcomes in research, diagnostics, and biotechnology.

Fundamentals of Microbial Culturing

At the core of all culturing lies media preparation, sterilization, and inoculation, tailored to the organism’s nutritional and environmental needs. Media supply essential nutrients: carbon sources like glucose, nitrogen from peptones, and minerals. For bacteria, complex media such as tryptic soy broth (TSB) or agar (TSA) support non-fastidious growth, while defined media with precise compositions are used for metabolic studies. Preparation begins by weighing dry ingredients accurately, for example, 15 grams of agar, 5 grams of peptone, and 3 grams of beef extract per liter for nutrient agar, dissolving them in distilled water with stirring, and adjusting pH to 7.0-7.4 using a calibrated meter and acids or bases. The mixture is then dispensed into tubes or flasks and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes at 15 psi to sterilize, cooling slowly to avoid cracks or bubbles. In fungal culturing, media like potato dextrose agar (PDA) or Sabouraud dextrose agar are common, prepared similarly but often at pH 5.6 to favor fungal growth over bacteria, with autoclaving times extended to 30 minutes for glassware to ensure sterility.

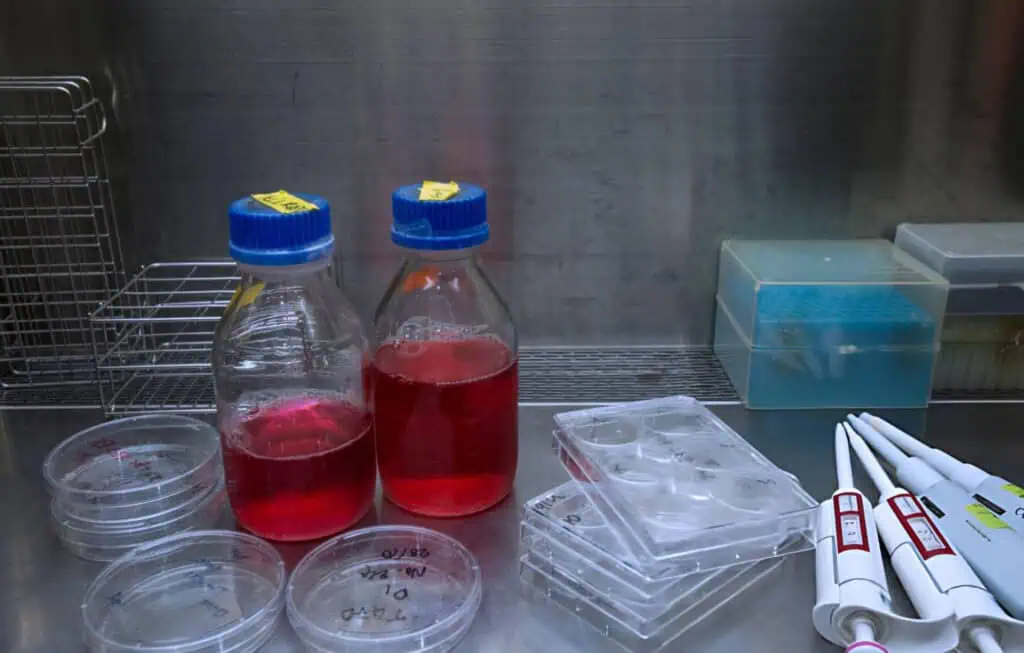

Sterilization is critical to prevent contamination, which can reach 10-20% in cocultures if not managed. Autoclaving is standard for heat-stable items, while filtration through 0.22-micrometer membranes handles heat-labile supplements like antibiotics. Dry heat at 160°C for two hours sterilizes glassware, and chemical agents like 70% ethanol disinfect surfaces. Aseptic techniques follow: working in a laminar flow hood, wearing gloves, and flaming tool necks and loops, heating an inoculating loop to red-hot in a Bunsen flame, cooling it briefly in air or uninoculated agar before use. For viruses, cell culture media like Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with fetal bovine serum (FBS) must be sterile-filtered, as contamination by mycoplasma can reduce viral yields by up to 50% in studies of influenza isolation.

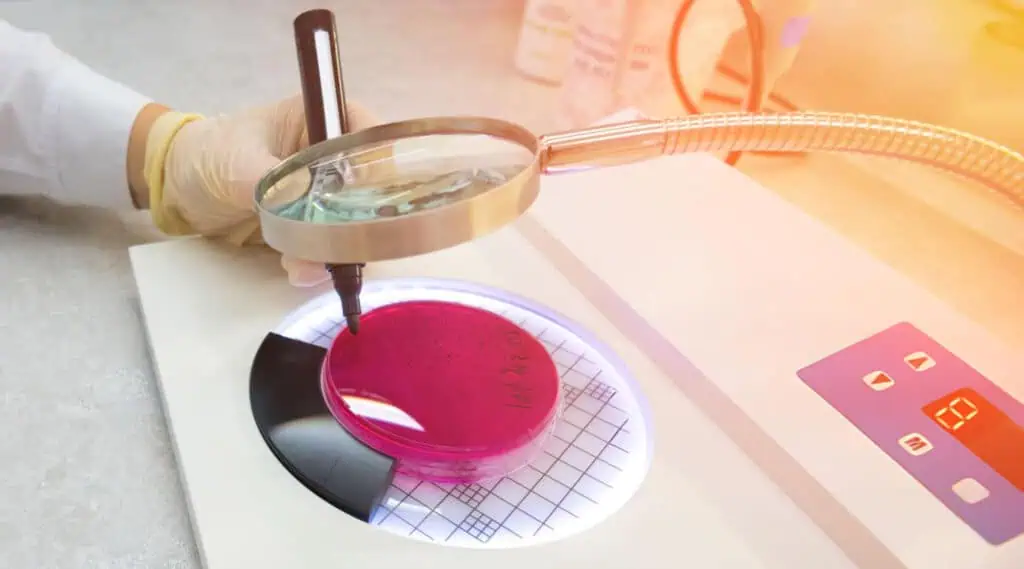

Inoculation introduces the microbe to the medium. For bacteria, a small inoculum from a colony or broth is transferred using a sterilized loop, mixing gently in liquid media or streaking on solid. Incubation follows under optimal conditions; 37°C aerobic for mesophiles like Escherichia coli, with growth monitored via turbidity, which indicates log-phase division after a lag period. In fungi, inoculation involves transferring mycelial blocks or spores to agar slants or plates, incubating at 25-30°C, where growth is visible in 1-4 weeks. Viral inoculation requires adding filtered specimens to cell monolayers, incubating at 32-37°C, and observing for cytopathic effects (CPE) like cell rounding, which can appear in 10-14 days for viruses like human metapneumovirus in Vero E6 cells. Accuracy demands controls: uninoculated media to check sterility and known positives for validation, ensuring contamination rates stay below 5% as reported in optimized clinical labs.

Bacterial Culturing Techniques

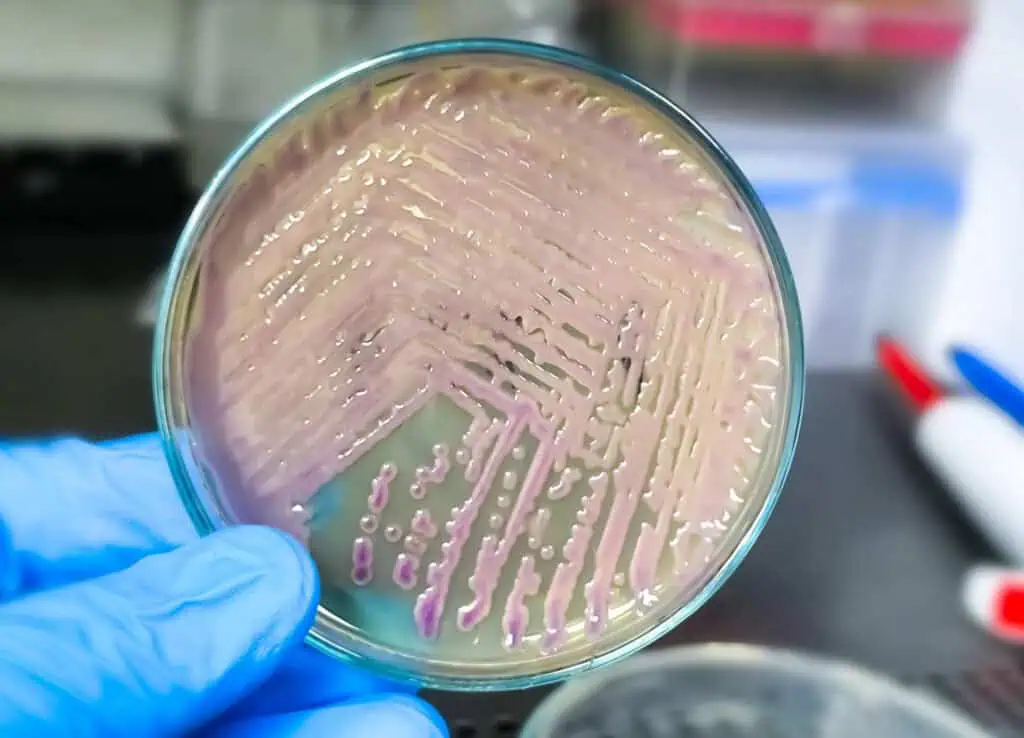

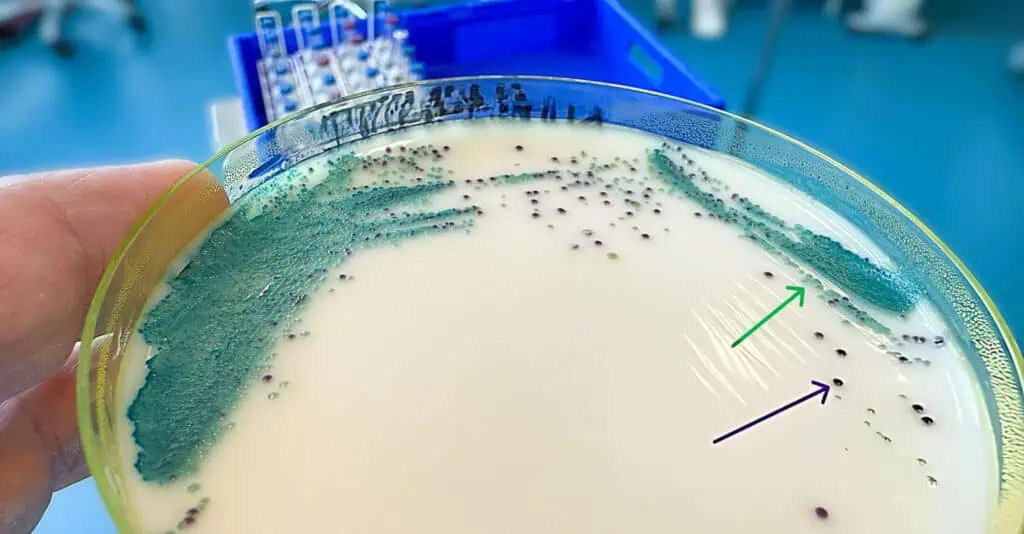

Bacterial culturing focuses on isolation from mixed samples to obtain pure cultures, essential for identification and susceptibility testing. The streak plate method dilutes cells across an agar surface for isolated colonies. Begin by flame-sterilizing a loop, cooling it, and picking a small inoculum from a broth or colony. Streak back-and-forth over one-quarter of a TSA plate, then flame the loop again, cool it in uninoculated agar, and drag through the first streak 3-4 times into the second quadrant. Repeat for the third and fourth quadrants, minimizing overlap to dilute progressively. Invert the plate and incubate at 37°C for 24-48 hours, selecting well-isolated colonies each from a single cell for subculturing. This method achieves high purity, with studies showing colony yields of 6.4 × 10^5 ± 3.5 × 10^5 bacteria per visible colony on blood agar for mycobacteria.

The pour plate embeds cells in agar for enumeration, including aerobes and anaerobes. Prepare serial dilutions of the sample in sterile saline (e.g., 10^-1 to 10^-6), add 1 mL of a dilution to a sterile Petri dish, pour 15-20 mL of molten nutrient agar cooled to 45-50°C, swirl to mix, solidify, invert, and incubate. Count colonies in plates with 30-300 for accuracy, calculating colony-forming units (CFU)/mL as colonies times dilution factor. Heat-sensitive bacteria may suffer 10-20% viability loss, but it’s effective for robust species like Bacillus, with recovery rates up to 80% in environmental samples. The spread plate spreads 0.1 mL of dilution on solidified agar using a sterile L-rod, drying briefly before incubation, yielding surface colonies ideal for enumeration.

Enrichment and selective culturing target low-abundance bacteria. For enrichment, inoculate samples into non-selective broths like selenite for Salmonella, incubate at 37°C for 18-24 hours to boost numbers, then subculture to selective agar. Selective media like MacConkey agar with bile salts inhibit Gram-positives, allowing Gram-negative recovery with 95% efficiency when supplemented with vitamins and hemin for anaerobes. Differential media, such as mannitol salt agar, highlight reactions like yellowing from Staphylococcus aureus fermentation.

For anaerobes like Clostridium difficile, use anaerobic jars with GasPak sachets generating H2/CO2, or glove boxes with N2/CO2/H2 mixtures. Prepare prereduced media with resazurin indicators, inoculate, seal the jar with an indicator strip (methylene blue turns colorless in anaerobiosis), and incubate at 37°C for ≥5 days. Recovery improves to 95% with fecal extracts, but challenges include overgrowth and inadequate jars for strict anaerobes. Fastidious bacteria like Haemophilus require enriched media such as chocolate agar with X and V factors, streaked and incubated in 5-10% CO2, with subculturing every 1-2 days to maintain viability.

Fungal Culturing Techniques

Fungal culturing addresses yeasts and filamentous forms, often from environmental or clinical samples, with techniques emphasizing humidity and nutrient specificity. For yeasts like Candida albicans, start by rehydrating lyophilized cultures: aseptically add 0.5-1.0 mL sterile water to the pellet, transfer to 5-6 mL water, let sit at 25°C for 1-2 hours, then inoculate YM agar or broth, incubating aerobically at 20-25°C. Growth appears in 1-2 days, with viability confirmed visually. For filamentous fungi like Aspergillus brasiliensis, rehydrate similarly, but sit at least 2 hours or overnight, then plate on Emmons’ Sabouraud’s agar at 20-30°C, avoiding sealed plates to promote sporulation and reduce sectoring.

Traditional methods include moist chambers: place leaf litter or dung on damp filter paper in sealed containers, maintain humidity, and check over 2-6 weeks for fruiting bodies in ascomycetes or slime molds, identifying via morphology. Success rates reach 50-70% for tropical leaf litter on selective PDA with antibiotics. Culture media techniques involve surface-sterilizing samples with 70% ethanol and sodium hypochlorite, homogenizing in sterile water, diluting, and spreading on PDA or malt extract agar (MEA), incubating at 25-28°C in the dark for 1-4 weeks. Subculture hyphal tips to purity, with recovery rates of 20-50% for bryophytes and 15-40% for deadwood, where Ascomycota dominate 60-80% of isolates.

Modern approaches integrate omics: extract DNA from samples, amplify ITS regions via PCR, sequence using Illumina, and use metagenomics to guide culturing on enriched media with growth factors like thiamine or siderophores. Co-culturing with hosts, such as pine roots for ectomycorrhizal Suillus spp., induces germination, with abietic acid boosting rates in four species. Studies show co-culturing yields novel compounds, like elsinochrome A from aposymbiotic Graphis elongata after 11 months, but challenges include contamination and slow growth, with uncultured fractions at 50-90% for symbionts.

Viral Culturing Techniques

Viral culturing relies on host systems, as viruses cannot replicate independently. Animal cell culture is primary: acquire tissues, dissociate with trypsin and EDTA, separate cells via centrifugation, seed into dishes with DMEM plus 10% FBS, and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2 to form monolayers. Inoculate filtered specimens, incubate at 32-37°C, and monitor for CPE using phase-contrast microscopy. Blind passages may be needed for slow viruses, with yields like 100-fold higher titers for parainfluenza in serum-free Vero cells.

Egg culture uses embryonated chicken eggs: inoculate into the yolk sac or allantoic cavity, incubate at 35-37°C, and harvest fluids after 4-7 days, monitoring lethality. Success is high for influenza, but labor-intensive. Animal inoculation adapts viruses to mice or rabbits, inoculating samples and monitoring replication, with titers reported as TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose), often higher than LD50 in studies. Challenges include mycoplasma contamination reducing yields by 20-50%, and biosafety, with primary cells like monkey kidney excelling for picornaviruses but harboring latent viruses.

Quantification, Interpretation, and Preservation

Quantification uses viable plate counts: dilute samples serially, spread 0.1 mL on agar, incubate, and count 30-300 colonies to calculate CFU/mL. For viruses, plaque assays dilute virions, overlay with agarose, and count plaques as PFU/mL, with titers varying 10^3-10^6 depending on cells. Interpretation correlates results with clinical data; e.g., >10^3 CFU/mL in urine indicates UTI, but false positives from contaminants like S. epidermidis reach 94% in blood cultures.

Preservation maintains strains: cryopreserve with 10% glycerol at -80°C or liquid nitrogen, thawing rapidly at 37°C. Lyophilization freezes with skim milk, dries under vacuum, and stores at 4°C, with viability lasting years but requiring 2-hour rehydration. Subculturing transfers to fresh media every 1-4 weeks to prevent mutations.

Challenges, Best Practices, and Ensuring Accuracy

Challenges include unculturable microbes (50% bacteria, 90% fungi in symbioses) due to dependencies, with contamination at 5-20% from overgrowth. Best practices: calibrate equipment monthly, use controls, document logs. Troubleshooting no growth involves richer media or condition checks; contamination requires retraining on asepsis. In clinical studies, pre-antibiotic sampling boosts yields, reducing false negatives, while rapid tools like MALDI-TOF cut ID time to hours.

Conclusion

Culturing techniques in microbiology blend precision and adaptation, yielding accurate results when steps are followed meticulously. From bacterial streaks achieving 80% recovery to fungal co-cultures unveiling novel compounds, these methods drive discoveries despite challenges like low cultivability. As omics integrate, culturing’s role endures, promising advancements in health and ecology.