Urinalysis stands as one of the oldest and most versatile diagnostic tools in clinical medicine, providing a window into the body’s metabolic, renal, and systemic health through a simple, non-invasive sample. This procedure involves the systematic evaluation of urine’s physical, chemical, and microscopic properties to detect abnormalities that may indicate conditions ranging from urinary tract infections (UTIs) to diabetes, kidney disease, or even malignancies. In an era of advanced molecular diagnostics, urinalysis remains indispensable due to its cost-effectiveness, rapid turnaround, and ability to screen for multiple disorders simultaneously. However, its reliability hinges on meticulous procedures and adherence to best practices, as errors in collection, handling, or interpretation can lead to false positives, unnecessary treatments, or missed diagnoses.

The history of urinalysis dates back to ancient civilizations, where physicians like Hippocrates examined urine’s color and sediment for signs of illness. Modern urinalysis evolved in the 19th century with the development of chemical tests, and today it integrates automated analyzers and standardized protocols to enhance accuracy. In clinical settings, urinalysis is performed billions of times annually worldwide, influencing up to 70% of medical decisions in primary care and emergency departments. Yet, challenges persist: studies show that up to 60-80% of urinalyses are ordered without genitourinary symptoms, leading to overuse and incidental findings that complicate management.

This article explores urinalysis procedures in detail, from sample collection to interpretation, emphasizing best practices for ensuring reliable results. Drawing on recent guidelines and research, including the 2025 American Urological Association (AUA)/Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) updates on microhematuria and consensus statements on UTI management, we provide a comprehensive, evidence-based guide. A dedicated section delves into real data from clinical studies on accuracy, prevalence of abnormalities, and diagnostic outcomes, highlighting the procedure’s strengths and limitations. By following these protocols, healthcare professionals can maximize urinalysis’s diagnostic potential, reducing errors and improving patient outcomes in diverse settings, from outpatient clinics to hospitals.

Fundamentals of Urinalysis

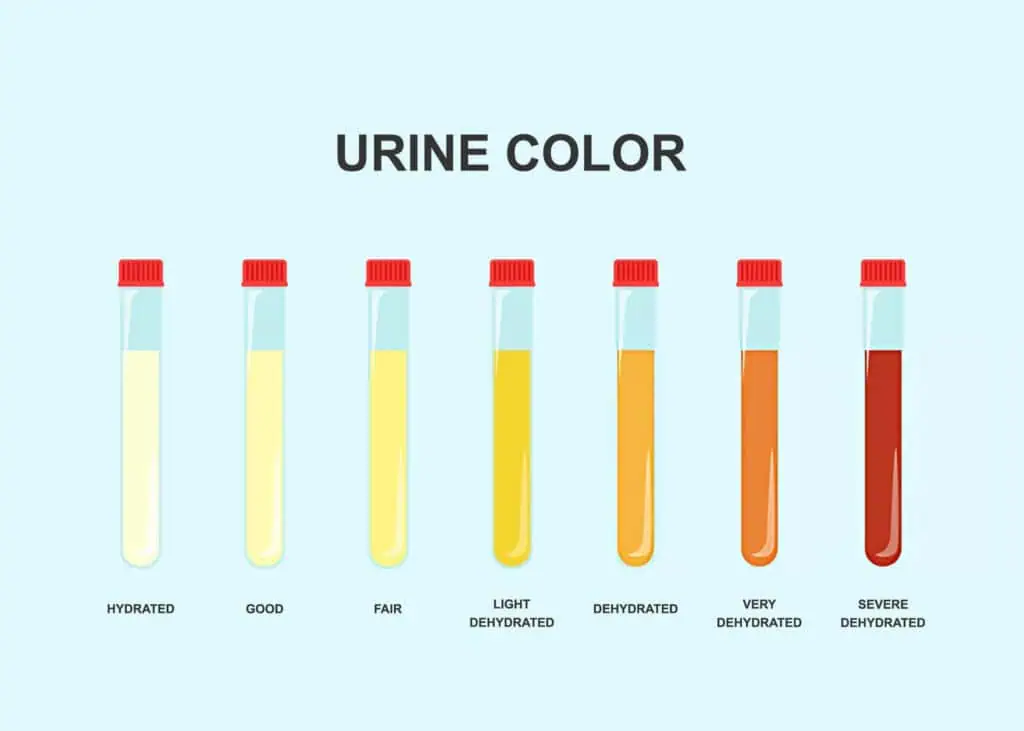

Urinalysis comprises three core components: physical examination, chemical analysis, and microscopic evaluation, each contributing unique insights into urine composition and pathology. The physical exam assesses macroscopic characteristics, offering initial clues. Normal urine volume ranges from 750-2000 mL per day in adults, with oliguria (<400 mL) signaling dehydration or renal failure, and polyuria (>3000 mL) indicating diabetes or diuretic use. Color varies from pale yellow (dilute) to amber (concentrated), but abnormalities like red (hematuria) or brown (bilirubin) warrant further investigation. Clarity should be clear; turbidity suggests infection, crystals, or lipids. Odor is typically mild, but ammonia-like smells point to bacterial urease activity in UTIs, while sweet odors suggest ketonuria.

Chemical analysis employs reagent strips (dipsticks) or automated analyzers to detect substances like pH (normal 4.5-8.0), specific gravity (1.005-1.030), proteins, glucose, ketones, bilirubin, urobilinogen, nitrites, and leukocyte esterase. pH deviations can indicate metabolic acidosis (low) or UTIs from urea-splitting bacteria (high). Specific gravity reflects hydration and renal concentrating ability; low values (<1.005) occur in diabetes insipidus, high (>1.030) in dehydration. Proteinuria (>150 mg/day) signals glomerular damage, while glucosuria (>180 mg/dL threshold) detects hyperglycemia. Ketones appear in starvation or diabetic ketoacidosis, bilirubin in hepatic disorders, and urobilinogen in hemolysis. Nitrites, produced by Gram-negative bacteria reducing nitrates, and leukocyte esterase, from white blood cell (WBC) lysis, screen for UTIs.

Microscopic examination involves centrifuging urine and viewing sediment under high-power fields (HPF) to identify cells, casts, crystals, and organisms. Red blood cells (RBCs) >3/HPF define microhematuria, WBCs >5/HPF suggest inflammation, and epithelial cells indicate contamination or renal tubular damage. Casts protein molds of tubules include hyaline (normal, <2/ low-power field) or cellular types signaling pathology. Crystals like calcium oxalate (envelope-shaped) may indicate stones, while bacteria or yeast confirm infection.

These fundamentals underscore urinalysis’s role as a screening tool, but interpretation requires context: patient history, symptoms, and confirmatory tests like culture for positives. Automation has improved efficiency, with analyzers processing hundreds of samples hourly, but manual review remains essential for atypical findings.

Sample Collection Procedures

Accurate urinalysis begins with proper sample collection, as contamination or degradation can skew results. Guidelines emphasize non-invasive methods for most cases, with invasive options reserved for specific needs. The preferred non-invasive technique is midstream clean-catch voiding: patients wash the genital area with soap and water, discard initial urine to flush contaminants, and collect midstream into a sterile container. This reduces epithelial cells and bacteria from the urethra, improving specificity for UTIs. For children or those unable to void voluntarily, bag collection is used, though it risks higher contamination rates (up to 50%).

Invasive methods include urethral catheterization, inserting a sterile catheter to drain urine directly from the bladder, ideal for immobilized patients or when clean-catch is unreliable. Suprapubic aspiration, puncturing the bladder through the abdomen, provides the most sterile sample but is invasive and used mainly in infants or obstructed cases. Collection timing matters: first-morning urine is concentrated, enhancing detection of abnormalities like proteinuria, while random samples suffice for screening.

Volume requirements are 10-20 mL for routine analysis, but 3-5 mL may work for targeted tests. Containers should be sterile, wide-mouthed, and labeled with patient details, collection time, and method. Prompt processing is critical; unrefrigerated samples degrade within 1-2 hours due to bacterial growth, altering pH, and forming crystals. If delayed, refrigerate at 2-8°C for up to 24 hours, or use preservatives like boric acid for cultures, though they may interfere with dipsticks. In 2025, guidelines for preoperative urological surgery, urine microscopy and culture (MC&S) are recommended ~2 weeks before procedures like transurethral resection, with antibiotics adjusted for positives to prevent complications.

Adhering to these procedures minimizes pre-analytical errors, which account for up to 70% of lab inaccuracies, ensuring reliable downstream analysis.

Physical Examination

The physical examination sets the stage for urinalysis, providing qualitative data that guides further testing. Volume assessment involves measuring output over 24 hours if needed, with abnormalities like anuria (<100 mL/day) indicating acute kidney injury. Color evaluation uses a color chart: dilute urine appears pale, concentrated dark yellow; red-tinged suggests hematuria or myoglobinuria, milky white chyluria from lymphatics. Clarity is assessed visually; hazy urine may contain phosphates (alkaline) or urates (acidic), while persistent turbidity signals infection or fat globules.

Odor, though subjective, offers clues: foul smells indicate bacterial decomposition, and fruity ketones in diabetes. Specific gravity, measured by refractometer or dipstick, evaluates renal function; values <1.005 suggest overhydration, >1.035 (corrected for glucose/protein) dehydration or syndromes like inappropriate antidiuretic hormone. These observations are quick and low-cost but must correlate with chemical and microscopic findings for diagnostic value.

Chemical Analysis

Chemical analysis quantifies urine constituents using dipsticks, multiparameter strips with reagent pads that change color based on reactions, read manually or by automated reflectometers for objectivity. pH pads detect acidity/alkalinity; abnormal lows (<5.0) occur in acidosis, highs (>7.5) in Proteus UTIs. Specific gravity pads estimate density, correlating with osmolality.

Protein detection uses tetrabromophenol blue, sensitive to albumin (>30 mg/dL trace); persistent positives require quantification via 24-hour collection or protein/creatinine ratio. Glucose pads employ glucose oxidase, positive in hyperglycemia; thresholds vary, but >100 mg/dL prompts blood testing. Ketones are detected via nitroprusside, indicating fat metabolism in fasting or diabetes.

Bilirubin and urobilinogen pads screen for liver issues: conjugated bilirubin positives suggest obstruction, elevated urobilinogen hemolysis. Blood pads detect hemoglobin/myoglobin, with sensitivity to 1-5 RBCs/μL; positives necessitate microscopy to differentiate intact RBCs. Nitrite pads identify Gram-negative bacteria, but negatives don’t rule out infection (e.g., Enterococcus lacks reductase). Leukocyte esterase detects WBC enzymes, positive in pyuria (>10 WBCs/μL).

Automation enhances reproducibility, but false positives from ascorbic acid (vitamin C) or menstrual blood require awareness. In 2025 UTI consensus, UA’s low positive predictive value for infection is noted, emphasizing culture for confirmation.

Microscopic Examination

Microscopic analysis examines centrifuged sediment (10-15 mL urine at 400g for 5 minutes) under low (10x) and high (40x) power. RBCs appear as biconcave discs; >3/HPF is abnormal, dysmorphic, suggesting glomerular origin. WBCs, round with granules, >5/HPF indicate inflammation; clumps suggest pyelonephritis. Epithelial cells: squamous from contamination (>15/HPF invalidates), transitional/renal from pathology.

Casts form in tubules: hyaline normal in low numbers, cellular (RBC/WBC) pathognomonic for glomerulonephritis/pyelonephritis, granular from degeneration. Crystals: uric acid (acidic urine), calcium oxalate (neutral), triple phosphate (alkaline, struvite stones). Bacteria: rod-shaped Gram-negatives or cocci; quantification (>10^5 CFU/mL in culture) confirms UTI. Yeast-like Candida appears budding; parasites are rare.

Polarized light aids crystal identification, phase-contrast dysmorphic RBCs. Automated flow cytometry analyzers count elements rapidly, but manual confirmation is needed for atypicals. In microhematuria guidelines, microscopy confirms dipstick positives, defining >3 RBC/HPF as significant.

Prevalence, Accuracy, and Diagnostic Outcomes

This section presents empirical data from clinical studies and guidelines on urinalysis abnormalities, accuracy, and diagnostic performance, drawn from peer-reviewed sources to illustrate real-world reliability.

Prevalence of abnormalities varies by population and context. In a 2022 study of 70,822 Chinese children, the overall prevalence of abnormal urinalysis was 4.3%, with isolated proteinuria (1.5%) most common, followed by isolated hematuria (1.4%) and leukocyturia (0.8%). Girls had twice the risk (odds ratio 2.0), and prevalence peaked at ages 12-14 years. In asymptomatic premenopausal women, a 2015 study found high rates of abnormalities even with ideal collection: leukocyte esterase >trace in 50% (midstream) and 35% (catheterized), WBCs >5/HPF in 50% and 27.5%, bacteria in 77.5% and 62.5%. Culture contamination exceeded 77% midstream 63% catheterized, highlighting false positives in healthy individuals.

In older adults with urinary stones, a 2022 AUA analysis of Medicare data (n=9,326) showed 33.9% with two concurrent 24-hour urine abnormalities, 35.2% with three, 15.8% with four or more; common issues included hypercalciuria and hypocitraturia. For UTI-symptomatic women, a 2025 meta-analysis reported STI co-prevalence of 23% (9-53% range), with Trichomonas vaginalis (18.8%), Chlamydia trachomatis (13.3%), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (4.5%) frequent; only 4.7% of STI-positives had positive cultures. Asymptomatic bacteriuria prevalence is 3-5% in young women, rising to 20-50% in the elderly, according to 2016 reviews.

Accuracy metrics reveal strengths and limitations. In a 2023 study of older women, urine biomarkers like azurocidin showed 86% sensitivity (95% CI 75-93%) and 89% specificity (82-94%) for UTI vs. asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), outperforming pyuria (AUC 0.92 vs. 0.80). A combined biomarker-pyuria model improved discrimination (AUC 0.95). For dipstick urinalysis in clean-catch samples, a 2025 review found sensitivity varying by age/sex: lowest in neonates (53.3%), highest in adults; overall for UTI, nitrite sensitivity 50% (low) but specificity 98%.

In bacteremic UTI, a 2025 pediatric study reported abnormal urinalysis sensitivity of 83% (76-90% CI), with 95% of normal UA having Gram-negative pathogens. Automated sediment analyzers like UriSed achieved 83.3% accuracy for leukocytes, 76.8% for bacteriuria, and 85.1% combined. For culture prediction, a 2024 machine learning study using urinalysis data achieved 85-90% accuracy in distinguishing positive cultures.

Diagnostic outcomes highlight clinical implications. In a 2021 analysis of 215 million U.S. tests, ambient temperature affected 90% results, with 5°C warmer days increasing creatinine 0.018 mg/dL, decreasing neutrophils 0.031×10^9/L, shifting lipids (HDL +0.97 mg/dL, LDL -2.90 mg/dL), and reducing statin prescriptions 9.7% on colder days. In COVID-19 admissions, abnormal urinalysis predicted ICU/death risk at 63.7% vs. 27.9% normal. Clinician diagnostic accuracy for UTIs averaged 56.9% (34-95%), for STIs 47% (26-75%). These data emphasize urinalysis’s utility when interpreted contextually, with high specificity for certain markers but variable sensitivity requiring confirmation.

Best Practices for Reliability

Best practices encompass pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases to ensure reliability. Pre-analytically, educate patients on clean-catch; use first-morning samples for concentration. Store refrigerated if delayed >2 hours; avoid preservatives interfering with tests. In the 2025 UTI consensus, the recommendation is against routine PCR for UTIs in post-acute care due to overdiagnosis.

Analytically, calibrate analyzers daily; confirm dipstick positives microscopically. For microhematuria, AUA 2025 guidelines mandate >3 RBC/HPF on a single specimen, repeating after benign causes are resolved. Use stewardship for cultures: only if symptoms/pyuria, per 2022 guidance, reducing unnecessary tests.

Post-analytically, correlate with history; avoid treating ASB except in pregnancy/urology procedures. In preoperative urology, test 2 weeks prior for high-risk procedures, treat positives. Quality controls: proficiency testing, staff training. These practices minimize errors, optimizing diagnostic yield.

Common Errors and Troubleshooting

Common errors include contamination (high epithelial cells), delaying analysis (bacterial overgrowth), or misinterpreting artifacts (crystals from storage). Troubleshooting: recollect for contamination, refrigerate promptly. False nitrite negatives from non-reductase bacteria; confirm with culture. Ascorbic acid interferes with blood/glucose pads; note supplements. In pyuria without bacteria, consider sterile pyuria (TB, stones). A systematic review ensures an accurate diagnosis.

Advanced Techniques

Advanced urinalysis integrates flow cytometry for automated counting, molecular tests for rapid pathogen ID, and biomarkers like NGAL for acute kidney injury. In 2025, AI predicts culture results from dipsticks, enhancing efficiency. Phase-contrast microscopy differentiates cell types, while polarized light identifies crystals. These augment traditional methods for complex cases.

Conclusion

Urinalysis procedures, when executed with best practices, yield reliable diagnostic results essential for patient care. From collection to interpretation, precision mitigates errors, as evidenced by real data on prevalence and accuracy. As guidelines evolve, embracing these protocols ensures urinalysis’s enduring value in medicine.